Beirut can be likened to a complex recipe of strong clashing flavours that are difficult

to combine in the same dish but that ultimately need to blend in the mouth. Eighteen

communities, eighteen religions and eighteen private laws constitute the city’s social

fabric, and these elements are both our richness and the source of our problems. Today once

again the balance wavers dangerously and the flavours are too strong to mix in the same

dish. The footprints of history have been erased and now it’s impossible to concoct the old

recipe for the future.

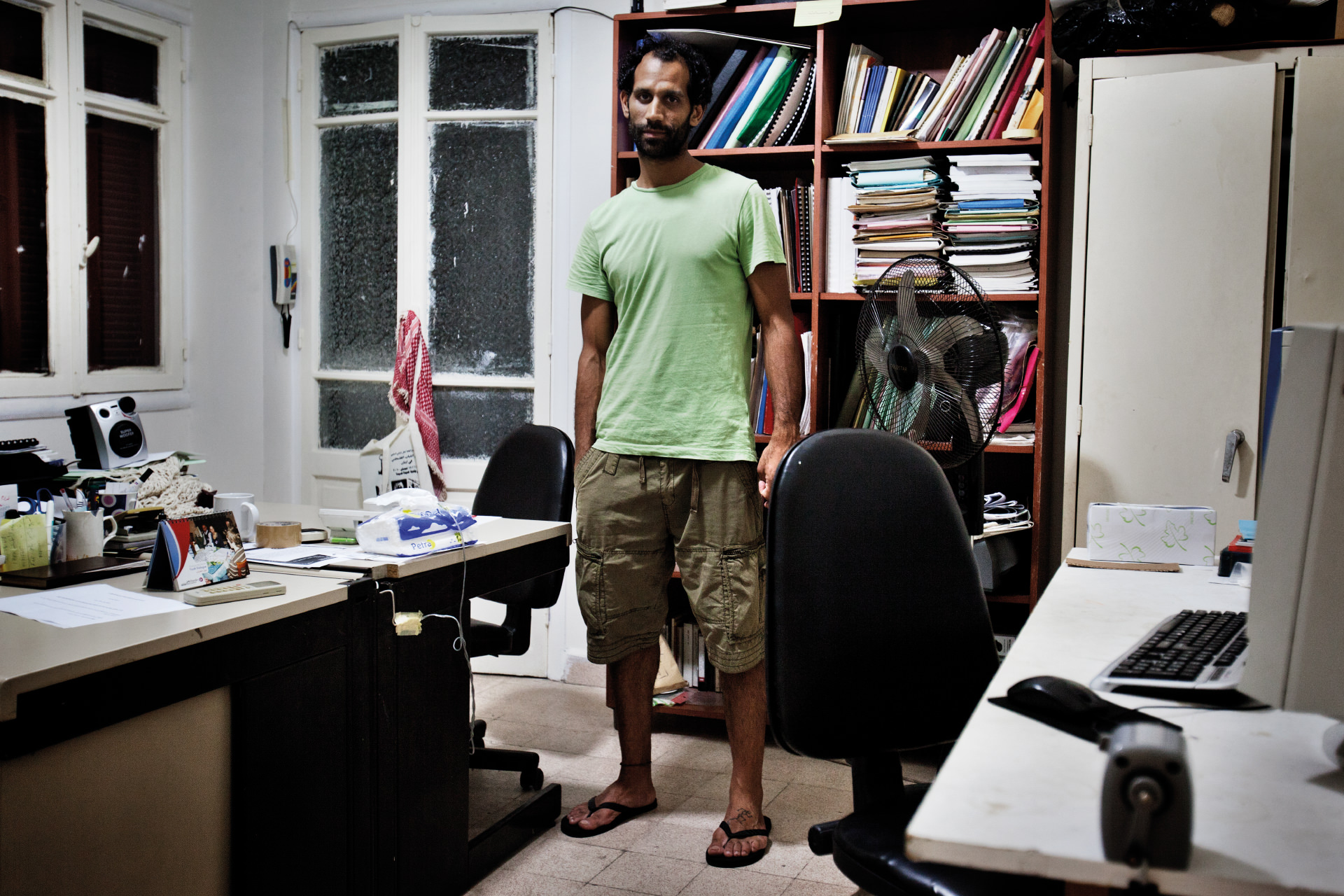

Beirut is a highly cultural city of underground movements. Historically the city has been a

haven for many people across the Middle East. You would not have found the same freedom you

did here anywhere else in the region. But now nothing is left of that freedom, just a

longing for it. In a few years we have lost the thrill of the cultural effervescence of the

last century. Today you can only smell the acrid stench of a political plan to wipe out the

true essence of this city. The local authorities are demolishing old buildings and coffee

houses to build tower blocks, shopping malls and parking spaces. Beirut is losing its

multicultural tradition. By demolishing our buildings they are wiping away our memory.

It loses

its memory

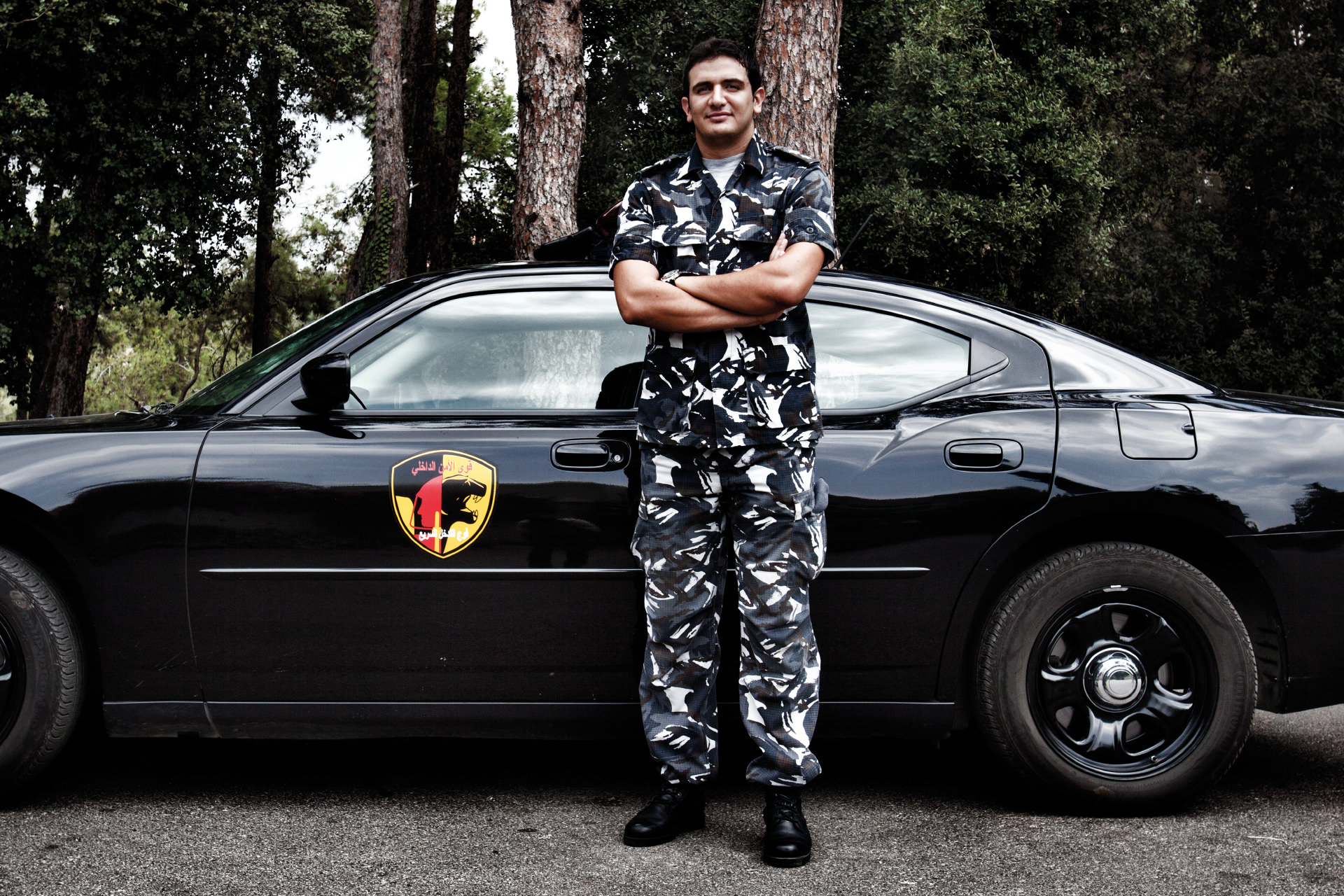

The former outline of the city has been disfigured by property speculation which is excused as a means of covering up the scars left by the war and recent conflicts. The new buildings have even erased the painful memory of these conflicts. The war is no longer discussed in the family, everybody knows it happened, everybody has been affected by it, but nobody talks about it. It is thus not surprising that sons end up making the same mistakes as their fathers. Even though they find themselves surrounded by traces of the past that should promote understanding and inspire progress, people would rather just forget. We are experiencing high levels of depression in the aftermath of the war triggered by Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and consequentially a high frequency of prescription and recreational drug use, mainly among the young. Synthetic drugs were initially introduced by the military to enhance the troops’ resilience and boost aggressive behaviour in combat.

The 1990s saw a boom in the distribution of these drugs to ex militia to buy their

silence over the war crimes they witnessed. Over and above their military use, these drugs

have become a recreational legacy of the conflict, evoking the excitement of combat whilst

easing and erasing the traumas of that time.

Alberto D'Argenzio